As the heart of the AMENDS project Facility asked many friends and leaders in the Chicago community to contribute to “Letters to the World Toward the Eradication of Racism.” Below is the letter we sent and a selection of what we got back.

If you are so moved, please contribute in your own way, and on your own timelines to the AMENDS project. Identify the pieces of yourself that have contributed to holding our society back from genuine equality and equity. See them, say them and then share them (with #AMENDS) to hold yourself accountable and to contribute to the eradication of racism.

Make #AMENDS

———

Re: “Letters to the World toward the Eradication of Racism”

June 9, 2020

At this moment, we as individuals, and we as Facility in collaboration with our communities, must be an active part in the eradication of racism. While this goal has always been embedded in our practices, now more than ever that intention needs to become action.

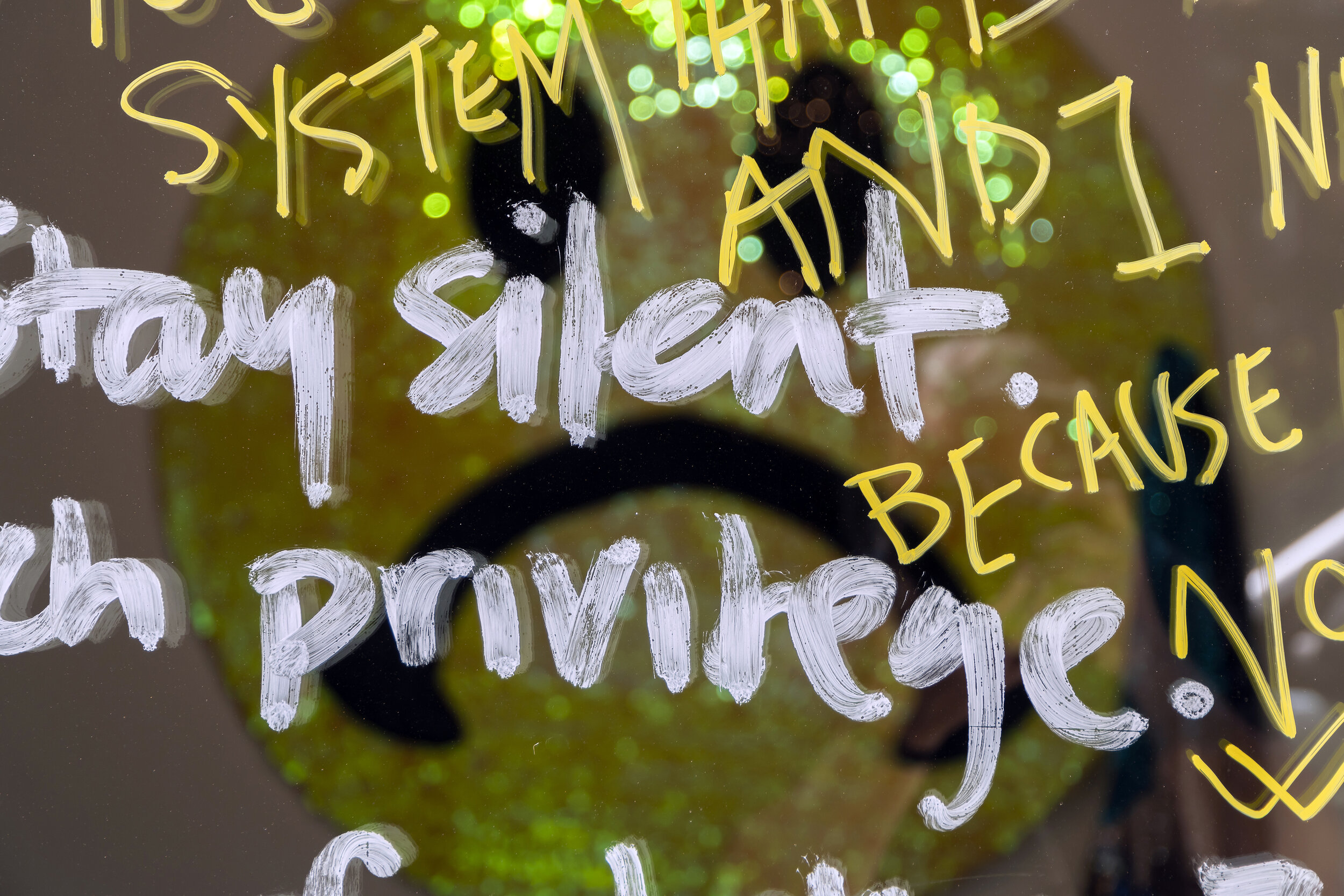

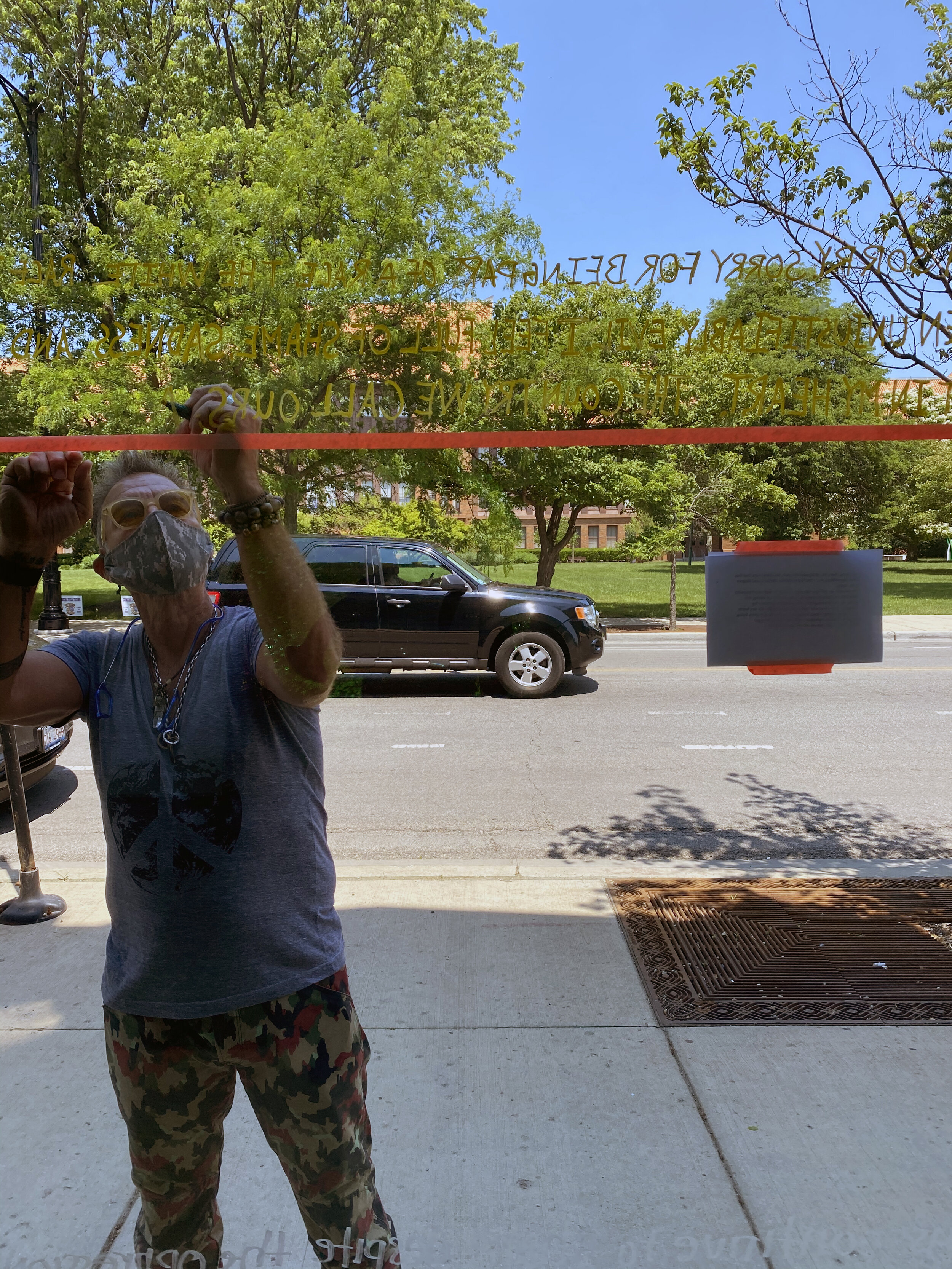

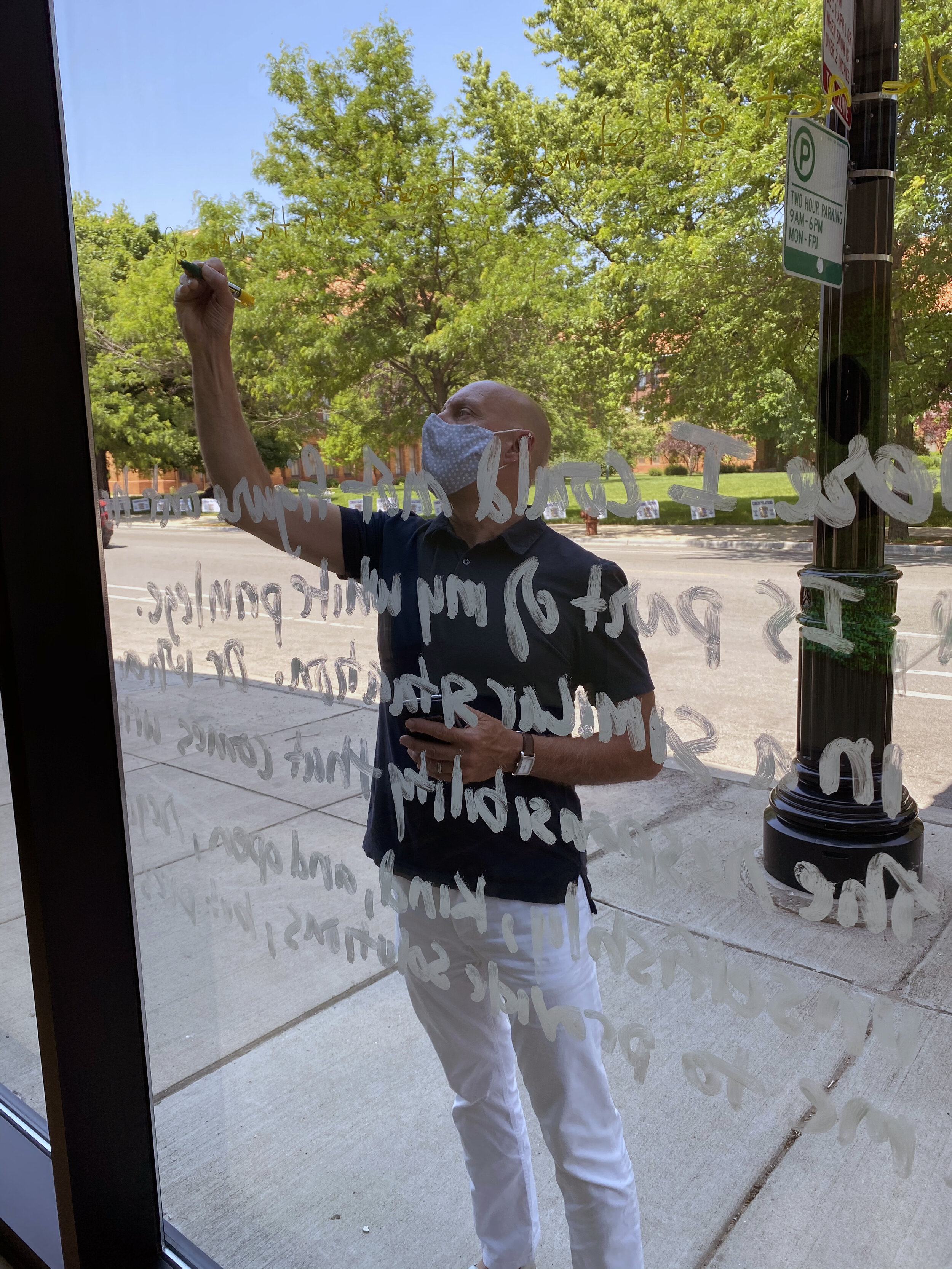

We are in the process of creating a multi-part project called “Amends” that originates at Facility and connects across Milwaukee Avenue to the public lawn of our neighbor, Carl Schurz High School. At its heart, the project’s goal is to ignite change through collected individual actions, by confronting and making public the many ways each of us has contributed to racism. It is a simple but personally confrontational act of looking in the mirror and acknowledging where each of us can each make necessary changes for the good of all people immediately, but even more so for the empowerment and success of our successors, our children.

We will use Facility’s storefront windows for public facing, unapologetically transparent letters to the world from individuals like you from our personal and profession circles, that bring to light their roles around racism through acknowledgments, confessions, and apologies. Those who come from especially

privileged backgrounds have enormous responsibility in this moment. They must be more than allies, they must actively root out the truths so long buried and ignored, beginning with self.

“Those born into privilege like myself are part of the problem until we commit to being part of the solution. Regardless of where on the spectrum the offense lies, all racist actions contribute to the continuation of this malignancy. Often, what we as white people see as light hearted or even funny are the daily offenses that don’t get checked publicly. We need to commit to anti-racist actions without fear of making mistakes or saying the wrong thing. Our missteps and subsequent corrections will allow more light to be shone on the problem and for real change to take root.”

— Bob Faust

We need your voice to be part of this project. We are asking for you to contribute a letter, a quote or a note as well as your time to actually write this on our windows. This is urgent, so also ask that you commit now for an install date the week of June 15 at your convenience. We will do all possible to ensure your safety and instate all social distancing measures needed.

“As my heart continues to weep, my emotions continue to ask myself how can I be more purposeful. I rarely ask for you help but at this time I need yours.” — Nick Cave

This part of the “Amends” project will then be used as the starting point of the community-wide public project that asks any and all individuals to identify their own role in racism and make amends with our country’s citizens as well as themselves by writing these on yellow ribbons and then staking them in the front lawn of Schurz High School. With time and commitment we envision the lawn filled with thousands of these “amends” and the grass continuing to grow alongside this pubic collection and community correction.

With sincerity and respect,

Nick and Bob

Thank you for your thoughtful and often times very vulnerable contributions:

Akilah Haley

Amy Bluhm

Amy Eshelman

Angelique Power

Anke Loh

Carre Lannon

Courtney Lederer

David Greene

Elisa Tenney

Elizabeth Hayes

Ginger Farley

Justin Ahrens

Kahil El Zabar

Katrin Schnable

Lucy Slavinsky

Lulia Rodrigues

Marilyn Fields

Marshall Svendson

Michael Workman

Monique Meloche

Naomi Beckwith

Nathan Hoyle

Rob Rejamin

Ross Fiersten

Sandro Miller

Stephanie Sick

Tanner Woodford

Tanya Quick

Tony Karmen

Vicki Heyman

Zoe Ryan

Select texts

I grew up in a small predominantly white town on the east coast. When I was young, racism was common place among friends, their families, and my family as well. It took the form of name calling, ignorant assumptions, and judgements towards black people and other races. It was ingrained behavior and thought, born of a total lack of diversity. Moving to Chicago after high school, I quickly started to realize how toxic these unexamined notions were as I was plunged into a diverse environment for the first time in my life. When isolated physically and mentally, those different than you become the “other”, that kind of categorization is the root of mistreatment and cruelty. Once we collectively realize we are all just human beings, different backgrounds and ethnicities will foster expansion of the mind, not fear.

— Marshal Svendson

———

I am privileged.

My whiteness gives me an advantage. This is an undeniable fact that is hard to learn and easy to forget. This time, I will not forget.

The horrific and inherent truth is that privilege requires cruelty. It's toxic. For me to "get," you have to "give."

Laquan McDonald, Paul O'Neal, and Rekia Boyd gave everything.

While I cannot wish away my privilege, I acknowledge it, apologize, and commit to justice in any way that I can.

A better world is possible. I will listen, and be a part of building it.

— Tanner W.

———

Even in New York, one of the world’s most diverse cities, the Stuyvesant Town of the 1950’s that I was born into was entirely White. As a child, when a Puerto Rican New Yorker crossed 14th Street into “my” neighborhood, I thought of them as “invaders” with no attempt to know them or think about their lives. It wasn’t until high school, during the civil rights era of the 1960’s and my first friendships across racial difference, that I understood how wrong the discriminatory racist feelings I’d inherited were. A first amends, a first unlearning.

At this moment, there are other amends to make, new challenges to unlearn, and many questions to pursue. And that pursuit will have to be more important than knowing the answers in advance. It feels—not scary, exactly—but consequential. Heavy. Acknowledging that weight, I immediately want to decenter myself, my White self. I want to be informed by my better angels without applause. I want to will take action without authorship. To sign this letter without a sense of achievement.

— Elissa Tenny

———

I WAS RAISED AS A WHITE SUPREMACIST

in a violent, physically abusive household that instilled in me the values of hatred, fear and despair. As a young white schoolboy, when another black boy or girl raised their voice at me, I thought nothing of giving them a smack in the face. I simply believed this was the way of the world.

Years later, as I found the ability to de-program my self and end the cycle of casual violence toward others, this ill empowerment of a despotic and sick soul, I discovered that I had not been wrong, that this has indeed been the way of the world for centuries.

My hope now is for the final and permanent destruction of that world, an eradication of all it represents so that we may replace it with one capable of nourishing and valuing not only my life, but the lives and prosperity of us all in the human village.

If *I* can change myself, it gives me hope eventually we may discover this new world -- together.

— Michael Workman

———

WHEN WILL WHITE PEOPLE LEARN TO LISTEN AND NOT BECOME DEFENSIVE ABOUT AN ENORMOUS ISSUE WE ARE CAUSING?

WE MUST ACKNOWLEDGE THE BLACK EXPERIENCE AND HOW IT IS TAINTED BY EVERY INSTITUTION IN AMERICA/THE WORLD.

— Nathan Hoyle

———

My white privilege needs to be checked—in my every thought and action. I need to dig deeper, self-reflect and commit to growing and changing the systematic racism embedded in my mind and body. I need to claim my racism. I need to listen more. I need to be louder. I need to demand more. I haven’t been loud enough. enough is enough. Why did it take until now to move us toward change? Over who else’s dead body? Enough is enough. ENOUGH. We white people need not just use our words, our banners, our posts and expect change. Our words are empty until we live and breathe them. Breathe. Breath. His breath. He couldn’t breathe. Her breath. She can’t breathe. We can no longer remain silent. I will not remain silent. We must carry that weight. I will carry the weight. We must be the change.

— Cortney Lederer

———

I was born into a white middle-class family in a small town in Germany. Growing up in my limited environment of family and a few friends from other countries, I never appreciated what kind of difficulties they might face. Even though we played, learned and partied together, I never thought they were being treated differently from me, perhaps because I never stood in their shoes. Moving to Chicago improved my exposure and understanding, when I began to interact with friends, students and colleagues who actually spoke about issues of inequality. I now realize how woefully inadequate my understanding of racial bias has been. Inaction, silence and not questioning the status quo is a crime. My outlook has been transformed. I am encouraged to be more courageous and rise to the challenge by asking questions and actively being part of the solution.

With Love, Anke Loh

———

Listen. You better think hard before sheltering in righteous outrage over the racist actions of others. You have been the others. You surely will be again. Ignorance is measured on a sliding scale, not pass fail. Every person you know denies being racist. Yet, here we are… racism so deeply rooted that three other officers gracelessly watch the casual murder of a black man, as if it were an embarrassing joke being told by an uncle in mixed company. Look at these others now, stunned and squinting in the light of our outrage. Think hard about the multitude of tolerated things that must be in place to create that horror scene – there are as many as the words in your spoken language - as many as the cells in your body. Is there anything normal about America’s normal? Is there anything normal about you?

— Rob Rejman, Note to Self

———

Dear Megan,

Systems built against humanity have socialized you into feeling powerless.

So, unlearn systems by building for humanity instead.

Sincerely,

Higher Self

— Megan Rejman

———

“The expression of one’s voice, their action and the simple act of standing together in the name of both justice and compassion contains both a power to heal and a powerful force to elicit change”.

— Tony Karman

———

Sometimes the searing light of the truth of systemic white supremacy makes it through the leaden armor of whiteness that encases me. I have white skin, I have white privilege, and I have white blindness. I am finding that I’m further armored by liberalism. I have deluded myself by thinking that because of my views and the way that I was raised that I was somehow an automatic ally. I have a long way to go before I can earn that, be that. I’m in for the work.

— Ginger Farley

———

"We cannot simply check-off dismantling racism. Race work is not a race, it's life's work."

— Akilah Halley

———

Silent. I have been silent in situations where I could not figure out how to act. I recognize that this posing no risk for me is part of my white privilege. Yet harm can come to a person of color in a similar situation. Or when I stay silent. I failed to see the inequality in that. And the responsibility that comes with such privilege. So I must raise my awareness to act unselfishly, kind, and open, regardless of whether I can figure "it" out or not. It is not upon me to provide solutions, but presence. Presence of heart.

— Katrin Schnabl

———

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” — James Baldwin

Sadness. Remorse. Discomfort. These are feelings I experience when I confront the chasm in my knowledge and understanding of the depth of racism that surrounded me in my 60 years of life. In writing this letter, I find myself thinking about my earliest memories…

I grew up in Ashland, Kentucky in a racially segregated town. Mine was a small-town, southern childhood that was rife with symbolism from the “Old South”. Our maid was a Black woman named Jessie. Jessie cleaned our home and cared for me as a little girl. I loved her very much. Our bartender for family parties and events was a Black man named Ben. Ben had a beautiful smile and was a true “Southern Gentleman” who possessed that enveloping charm long exalted as “Southern Hospitality”—he made those special occasions so memorable. And our family deeply respected him.

In writing this letter, I must not let this anecdote from my childhood end without asking a painful question:

Despite my love for Jessie, despite our family’s deep respect for Ben, would this Black woman and Black man have come into our lives if they had not worked for us? The answer is no. And while I was only a child, while my family raised me in a home without overt racism, the culture of the South and America at large was inherently racist. Yes, I was a child and a product of my surroundings. But I am ashamed to say that it would be many years into my adulthood before Black men and women entered my life as cherished friends, mentors, and members of my chosen family.

For much of my life, I accepted the world as I saw it. I did not ask questions. I did not seek answers. I did not engage. I did not amplify. I did not take action. I am deeply sorry. I must do better.

Even now, in writing this letter, I want to share with you the ways in which my life changed when I stopped turning away from injustice—when I started to engage—when I took action. But this letter is about examining hard truths, not celebration. Even as I began to become more conscious of systemic racism and the injustice faced by our Black and brown community members, I still had and have chasms in my knowledge and understanding. For example:

20 years ago, I bought an Aunt Jemima cookie jar at a flea market. As a collector of cookie jars, I viewed this as a piece of “kitschy Americana” and displayed it in my home without a second thought. Even though the purchase wasn’t made with malice, even though the display wasn’t meant to provoke pain, I must ask myself “Why didn’t I know this was wrong?” “Why wasn’t I curious about the imagery of this Black woman and what she was meant to represent?” “Why did I just accept that this was ok?” “Why does white America use Black imagery without understanding the historical context?”

When I was challenged on displaying this cookie jar, I finally learned the history of Aunt Jemima. The R.T Davis Company based Aunt Jemima on a real person, Nancy Green. Nancy was born a slave in my home state of Kentucky in 1834 and she portrayed Aunt Jemima as a live model until her death in 1923. Green’s portrayal was shaped by the racist cultural stereotype of a “Mammy” and it is the most well known and enduring stereotype of Black women.

Yes,I bought this Aunt Jemima cookie jar without knowing the racist and deeply painful history of this imagery. But I must ask myself “Why didn’t I know?” Is it because I am a white woman and that has afforded me the ability to remain ignorant of the insidious manner in which racism shapes so much of the imagery and portrayals of Black women in our culture? The answer is yes.

It is not enough to be sorry—I must examine the ignorance that informed my actions and unlearn the unconscious biases that guided those actions. In order to move forward in my commitment to practice anti-racism, I must stand in my discomfort with my eyes and ears open. This is uncomfortable. I feel shame. “...but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

I’ve learned that you shouldn’t go through life with a catcher's mitt on both hands. You need to be able to throw something back.” — Maya Angelou

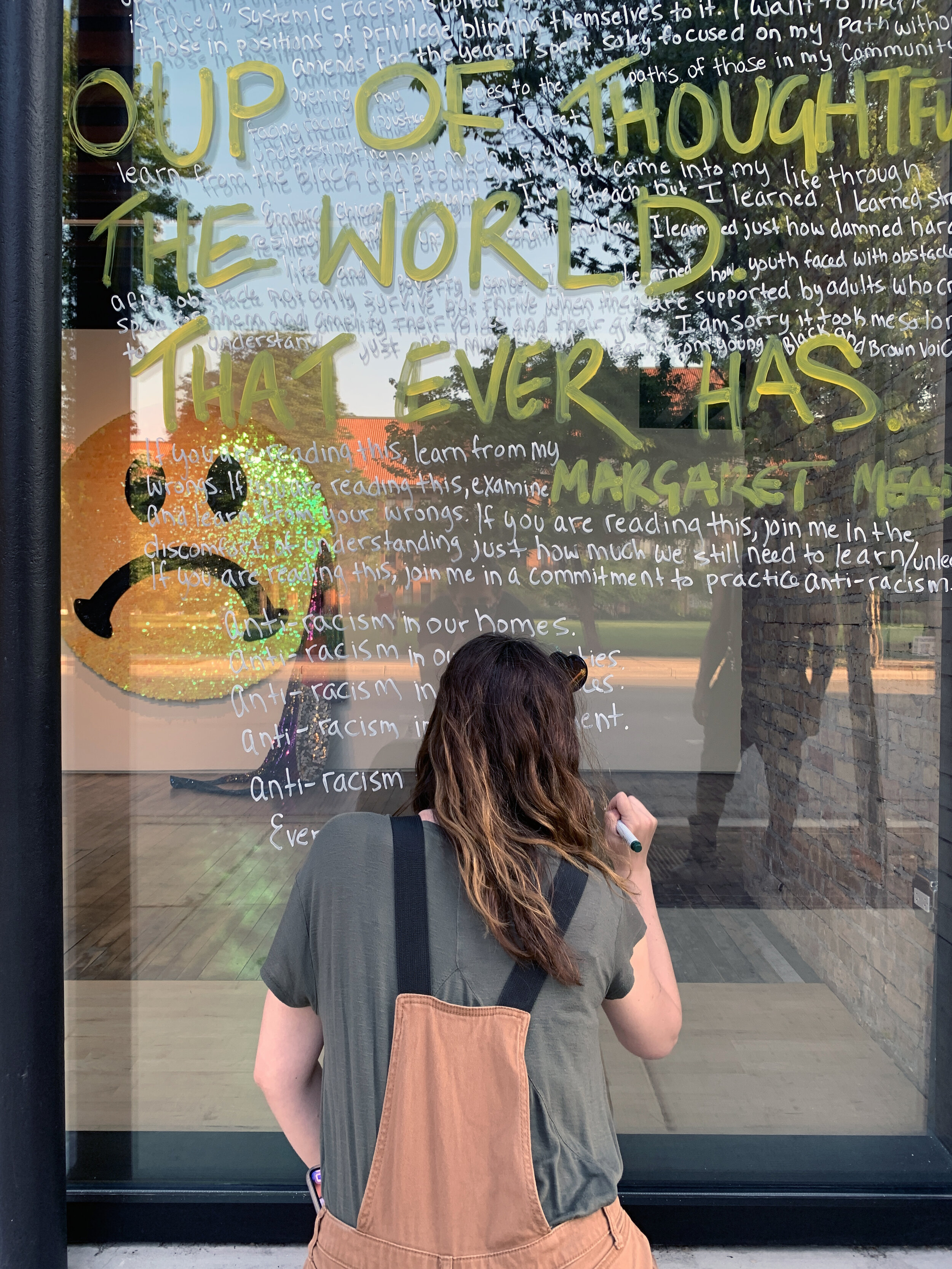

Systemic racism is upheld by both those actively working to maintain it and those in positions of privilege blinding themselves to it. I want to make amends for the years I spent focused solely on my path without opening my eyes to the paths of those in my community facing racial and economic injustice. I know now that this kind of blindness also hurts the one who cannot see. I am committed in my anti-racism to sharing the stories of how opening my eyes, my ears, and my heart for connection allowed my path to cross with Black and brown youth from our city and how the good I did for them was monumentality surpassed by the good they did for me.

I regret underestimating how much I would learn from the Black and brown youth that came into my life through Embarc Chicago. I thought I would teach—but I learned. I learned strength, resiliency, and unconditional love. I learned just how damned hard life and poverty can be. I learned how even young people faced with obstacle after obstacle not only survive but thrive when they are supported by adults who create space for them and amplify their voices and their gifts. I’m sorry it took me so long to understand just how much I could learn from young Black and brown voices. If you are reading this, don’t wait any longer to learn this lesson.

If you are reading this, learn from my wrongs.

If you are reading this, examine and learn from your wrongs.

If you are reading this, join me in the discomfort of understanding just how much we still need to unlearn.

If you are reading this, make amends.

If you are reading this, join me in a commitment to practice anti-racism.

Anti-racism in our homes.

Anti-racism in our communities.

Anti-racism in our workplaces.

Anti-racism in our government.

Anti-racism together.

Every.

Day.

— Vicki Heyman

———

My blood is half German and half Southern, which means I am of 100% racist ancestry. And yet, growing up in the south, I came to identify more with black culture than white. Or I should say, I came to identify with those outside of power- - the outsiders, trying to be different, to have style and expression that was their own voice, to be evolution. Which in the south, meant blacks and jews and women. As one of two daughters growing up in the middle class 70s, I also was raised to believe in bootstrapping optimism. If you work hard, if you keep your nose to the grindstone, if you believe in yourself, you can do anything kind of optimism. The power of positive thinking. And as I've grown into a professional woman, I've surrounded myself in a bubble of the same. I've led my team with that strategy. I've showed up to work, and life, every day with that attitude. I've listened and read and sought those who subscribe to optimism. Together with curiosity, it has become the closest thing to my identifying culture. The problem with optimism is that it is a form of blinders. It keeps you from seeing bias and injustice. It keeps you from hearing the truths of those who are working hard, and still can't get a leg up, because they are devalued through systemic and institutionalized barriers. It keeps you from anger. I feel betrayed by optimism. I am mad at my race. I am mad at my systems. I am angry at myself. This is not my story, this is not about me. And, yet, it is. Because I am inherently part of the problem. In my blind optimism. In my silence. In my lack of association with a group that I can change.As a brand consultant, I have used economics to argue for representation. What I see now is that I have been complicit in a culture that doesn’t respect black lives by arguing for their dollars, by using their image, and not just calling the system out for what it is—advantage white leadership. My privilege has been to be listened to. To be trusted with things I’ve never done because the system believes in white people’s skills. That privilege meant speaking to mostly white male CEOs and helping them paint a coating of “diversity” to buy more time for the system. Optimism let me think this is progress, while people are being lynched.

— Tanya Quick

———

I have been an advocate of equality since I was only two

but amends and reparations are seriously overdue

I am white, but I continue the fight

until a JUST world is our truth

— Monique

———

Dear Naomi,

A few years ago, an artist very dear to me made me commit to speaking my mind and meaning what I say. It was a performance work, theoretically, but the hope was that by performing forthrightness, I could make a life practice of being forthright. But I have to admit: I haven’t always spoken my mind, I have held my peace when I should have been fighting some battles. I must speak out, even if for a lost cause. No minds or behavior or language will change unless I speak up. If I were to be honest with myself, none of those things will change even if I do. But I don’t have a choice: I made a promise and I owe it to myself and the world I want to see.

— Naomi Beckwith

———

I'm a human being, I am white and I am racist.

None of these were my choice, but all put me in the center of a system that was built to help me succeed. I never questioned that system because it was working for me. Racism settled in me quietly, simply by my association with others in the same situation. The N word was used regularly in these communities and while I understood its' demeaning meaning and its' oppressive purpose by its context, it wasn't until I got older and chose to widen my communities that I connected the many incredible people that filled my world with the riches that make it worth living like art, music, dance, poetry, scholarship, and enlightenment as the very ones this word was being wielded against. Because I recognized this and loved them, I thought I was an ally, but I did not to back that title up. I misinterpreted my closeness with "woke"ness and misused my permissions by voicing inappropriate comments cloaked in bad humor. That had to hurt more deeply coming from me than the comments from others I also saw and let go through my complicent choice to be silent. I am sorry for these actions and inactions, and for not calling them out for what they are in myself sooner. And I am grateful for all the gifts black human beings and their culture continue to share despite the oppression and obstacles and we put in their way.

I thought I was a woke human being, but I am a white human being, and that makes me nothing more than a work in progress.

I promise to keep working.

With love and respect, Bob Faust